Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Fall 2025

The Fall 2025 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Andy Warhol’s Blue Liz as Cleopatra (1962) on the cover.

Fall 2025 Issue

Carlos Valladares tracks the artist’s engagements with Hollywood glamour, thinking through the ways in which the star system and its marketing engine informed his work.

Andy Warhol, Double Liz as Cleopatra, 1962, silkscreen ink and acrylic on linen, 21 ⅛ × 31 ¼ inches (53.8 × 79.4 cm)

Andy Warhol, Double Liz as Cleopatra, 1962, silkscreen ink and acrylic on linen, 21 ⅛ × 31 ¼ inches (53.8 × 79.4 cm)

I like American films best. I think they’re so great, they’re so clear, they’re so true, their surfaces are great. I like what they have to say: they really don’t have much to say, so that’s why they’re so good. I feel the less something has to say, the more perfect it is.

—Andy Warhol, in Cahiers du Cinémas in English, 1967

Andy Warhol, Silver Screen: can’t tell ’em apart at all.

—David Bowie, “Andy Warhol,” 1971

When Mickey Mouse met Andrew Warhola Jr., the seed of a star was born. An older Andy claimed that cartoons were not his thing.1 Ever the king of a poignant, hilarious contradiction, though, he would go on to say that his favorite actor was Mickey Mouse and his favorite actress was Minnie.2 Like many other working-class kids in 1930s Pittsburgh, the young Andy Warhola was enthralled by the world of motion pictures—not only the movies but also the newsreels, the cartoons, the munched-on popcorn, the movie magazines, the ranking of favorite gods and goddesses, the whole ritual. He was made for the underground—not just the underground New American Cinema, above which he would tower in the 1960s with Sleep (1963), Eat (1963), and Empire (1964), but also the great directors hidden in plain sight: Howard Hawks, early John Ford, Wild Bill Wellman, Don Siegel, Henry Hathaway. All these were improbable models for what little Andy would become when he dropped the last “a” in his name and became Warhol: “perfect examples of the anonymous artist, who is seemingly afraid of the polishing, hypocrisy, bragging, fake educating that goes on in serious art.”3

Once, Andy’s beloved mother, Julia, saved up all the earnings she had made from nine days of housecleaning work—about $9, or $215 today—to buy Andy one of those newfangled home movie projectors he so desired. She never told her husband.4 Thus sprang Andy’s clandestine, quiet passion, cinephilia. His inspired enthusiasm for the kind of movies that were then dismissed as “schlock,” and that today are laughed at and accepted only as “camp,” would continuously befuddle the art world over which he would reign in the ’60s. He especially shocked people in 1965, at the height of his branded popularity, by saying that he was retiring from his known-commodity media of painting and sculpture in order to make movies. It’s not hard to see why: had any of us been a fly on the wall in Julia’s house, watching her youngest son watch Mickey in The Band Concert (1935) and Thru the Mirror (1936), cut up magazines, and decorate a scrapbook with glossy headshots of Carmen Miranda, Mae West, Henry Fonda, and the beloved Shirley “Animal Crackers in My Soup” Temple—well, Warhol’s provocative declaration of his preference for cinema would have come as no mid-movie twist out of Alfred Hitchcock.5

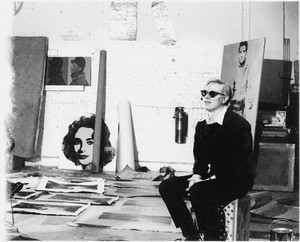

Andy Warhol with a Liz and an Elvis painting at the Factory, 231 East 47th Street, New York, c. 1965. Photo: Billy Name

Warhol came of age with Hollywood sound cinema. He was born in 1928, a year after Warner Bros. fatefully released the first feature-length movie with synchronized sound, The Jazz Singer, starring Al Jolson. As related in Blake Gopnik’s 2020 biography of Warhol, the naughty Kid Andy often snuck into cinemas past the ushers without paying the requisite 10¢—“the worst thing that Andy ever did,” according to John, his older brother.6 Before and during his time as a student at the Carnegie Mellon School of Art (then Carnegie Tech), Warhol would routinely attend the prodigious repertory screenings at the Pittsburgh art gallery Outlines; films as diverse as Leo McCarey’s Marx Brothers farce Duck Soup (1933), Jean Cocteau’s fairy-tale romance La Belle et la Bête (1946), Fritz Lang’s German sci-fi freakout Metropolis (1927), and the early experimental work of Joseph Cornell and Maya Deren were all shown at Outlines and all made a considerable impact on the teenage Warhol. Parker Tyler, whose classic film histories The Hollywood Hallucination (1944) and Magic and Myth of the Movies (1947) cemented him as one of the earliest serious thinkers on Hollywood, gave numerous lectures at Outlines that piqued Warhol’s later personal and intellectual interest in stardom.7 And as Gopnik relates, one particular filmed allegory—the debut of the left-wing film noir master Joseph Losey—would hold particular resonance for Warhol in years to come:

At one art-student party . . . Warhol arrived with his hair dyed chartreuse—a sure reference to a new movie called The Boy with Green Hair. It premiered in November 1948 and starred the child actor Dean Stockwell, who as an adult would show up at a Hollywood party given for Warhol in 1963. The movie’s plot involves a twelve-year-old orphan who wakes up one day to discover that he’s become “different” from everyone else—because of his suddenly green hair—and has to learn to cope with discrimination and even beatings. Warhol and the [Carnegie Tech students] who watched him parade his emerald dye job could only have read this as a parable for coming out gay in Pittsburgh.8

Movies kept Warhol alive. The films of classical Hollywood and their nitrate allure fed his artistic imagination more than anything else did. His later cultivation of Superstars—Candy Darling, Viva, Pope Ondine, Edie “Poor Little Rich Girl” Sedgwick—was sneakily a cockeyed reimagining of the MGM star system: more stars than there are in heaven! All Warhol’s manic-compulsive repetitions of Marilyns, Elizabeth Taylors, and Elvises suggest, on the basic level, a film strip. Yet unlike a film strip, the great ’60s Warhol paintings do not show the figure in a pantomime of movement: They are touchingly frozen. It is only when he applies camp-ish mascara, and when the figures’ backdrops half-evoke the blank screens used in old Hollywood rear projection—but come in varying shades of piss-and-jaundice yellow, puke green, Vincente Minnelli red, the purple of an Upper East Side biddy’s shock of hair—that any (illusion of) bustle is magically restored into the cinematic painting’s field. Famously, Jean-Luc Godard drew our attention to the twenty-four frames a second in which a film lies to us about the fantasy that it moves, convinces us that we are observing living beings in front of us, when in fact we see only a trace of them trapped in an insignificant sliver of time—a mortal couple of near-gods, the Odysseus of Spencer Tracy and the Penelope of Katharine Hepburn, who can be conjured up long after death. Every time we watch or return to Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), Father of the Bride (1950), Flaming Star (1960), or The Misfits (1961), we begin a séance. And we witness the drugged, slowed-down, 16-mm film of the séance every time we face one of Warhol’s proliferating icons, which repeat in the manner of a child who, discovering how to draw, becomes fixated on a weird wild animal and must repeat its paws and fangs and fur over and over again, to confirm (pathetically) that it exists, that it once existed, that it might continue to exist.

Andy Warhol, National Velvet, 1963, silkscreen ink, silver paint, and pencil on linen, 136 ⅜ × 83 ½ inches (346.4 × 212.1 cm), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Elizabeth Taylor constitutes her own solar system. A star and its shine are never enough. So, taken as he was with one Liz, in Blue Liz as Cleopatra (1962) Warhol felt the need to fill the blue movie of his scrapbook mind with fifteen Lizes, four for each row and one tantalizingly left out of the last row. The backdrop is a bewitching moody blue, reminiscent of those tinted scenes in silent movies that take place in forests at night, when paramours scheme together under naked moonlight. The black-and-white image of Taylor, taken from a spread on page 40 of the issue of Life magazine for April 13, 1962, shows her off in her iconic Cleopatra makeup, with its Orientalist knife-blades of thick black lines around the eyes; the lack of color makes it impossible to note Taylor’s heavy blue eye shadow, dark-brown wig with bangs, and gold-inflected braids. But Warhol’s silent-film tinting in Blue Liz as Cleopatra suggests the deep blue of Taylor’s makeup in the finished film.

Certainly what appealed to Warhol was the fact that he was making his audience face—en fait, not a woman but the idea of a woman, playfully ribbing the quaint conservative presumptions of womanhood: the girl as mass-produced blank form for an art-world coloring book. This aesthetic battleground emerged through the face of one of the most famous and globally powerful women of all time, being played by her modern equivalent: the Hollywood superstar, paid $1 million to play-act, plus 10 percent of the film’s gross, plus $50,000 a week for every week that the play-actor was deathly ill from pneumonia and therefore couldn’t even play-act. Playing around with the signs of the day, Warhol immediately recognized that beyond the stiff, molasses-slow, talky mise-en-scène of Joseph L. Mankiewicz, the kook significance of an expensive hunk of celluloid like Cleopatra (1963) lay in its status as the quintessence of star ideology. A humble early-teen horse girl (the National Velvet Liz of 1944, which also piqued Andy’s curiosity and inspired a parallel series of works highlighting Taylor at twelve) wizens and grows up into a blazing symbol of power, sex, and modern transmedia poetry, a name that doubles as a quilt of gossip, marriages, and hype-machine intrigue. As the original Life caption has it, she is the quintessential femme fatale.9 And it took a Warhol, an acolyte of the church of cinema, to depict this with such sincere, unsignposted cheek. I emphasize the work’s poetry, for Liz is arranged and multiplied in Warhol’s blue field like the Esso gas cans in the “Filling Station” of another poetic Liz, Elizabeth Bishop, cans arrayed to “softly say / Esso—so—so—so.” And so Warhol’s rows of Lizes softly say, Miss Taylor—Lor—Lor—Lor.

It’s critical that Warhol culled his Liz from a Life spread. That lucky copy! Had it been picked up by anyone else—i.e., a nonartist—it would most likely have been gleaned through for the pictures, consumed and read quickly (if at all), then thrown in a bin, consigned to its status as an ephemeral object: the mass media weekly. Instead, Andy, like any good scrapbooker, preserved the pictures. He liked remembering. But he also worked with a mind seemingly machine-made for the automatic, a mind that nightly forgot the accomplishments of the day.

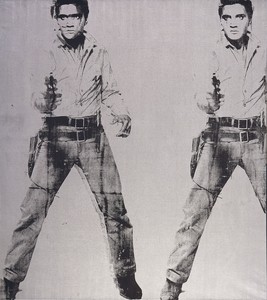

Andy Warhol, Triple Elvis [Ferus Type], 1963, silkscreen ink and silver paint on linen, 82 ¼ × 72 inches (208.9 × 182.9 cm)

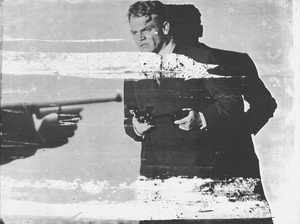

His portraits of James Cagney (1962) and the many Elvis Presleys (1962–64) were based on promotional photographs taken by anonymous photographers hired by movie-studio executives to sell (once again) not the man but the idea of the man. Cagney, fearful in his classic gangster suit but remembering his days as a hustling song-and-dance man (Footlight Parade, Hard to Handle, both 1933), looks panicked, about to be plugged by a tommy gun set to kill; Presley, nervous as he play-acts the big bad serious Hollywood actor but remembering his days as a song-and-dance man on the Ed Sullivan Show and Sun Records 45s, looks panicked, about to shoot his load.

The poet John Giorno (for a time Warhol’s lover), in Great Demon Kings (2020), his fantastic memoir of the art, love, and poetry of the 1960s, writes with delight about the day when he went over to Warhol’s and saw him drawing the cover for the October 20, 1963, issue of the New York Herald Tribune: a still life of a Coca-Cola bottle, a thermos, and a jar of Vaseline. As Giorno writes, “For gay men at the time, a jar of Vaseline meant one thing: anal sex. So I was thrilled at what I saw as secret homosexual subtext. ‘A Vaseline jar on the cover of the Herald Tribune! Andy, that’s so brilliant!’ ‘I need the seventy-dollars,’ [Andy replied]. . . . It was a gay image in mass media.”10 Let’s also recall what John Waters has said. Writing on the Liz paintings, Waters sees more than just those stodgy art-historical cliché ideas like “the accidental,” “the postmodern melancholy of Warholian form,” and “the markings of Abstract Expressionism”:

The other Double Liz (1963) is even more low-tech: terribly silkscreened. . . . We all know he lusted for fame, not sex, but one can’t help but wonder if Andy artistically “masturbated” to Liz’s Hollywood celebrity—the fame he feared he could never have. He did do “cum paintings” later in his career, so is it nervy of me to see a symbolic “facial” here? A semen paint deposit that just missed the right side of Liz’s head and was never wiped up by studio assistant Gerard Malanga with a Silver Factory “wankerchief”? A very sexually satisfying one-night stand that would be forever remembered by art history?11

Andy Warhol, Cagney, 1962, screenprint, 30 × 40 inches (76.2 × 101.6 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of UBS

Warhol always aimed high and low, far and wide. Perhaps that nice raucous night extended to the similarly “terribly silkscreened” early Cagney. Perhaps, too, in the throes of his artistic jerk-off, he had in his mind the picture of a straight-backed Elvis, gun aimed in his line of sight, shaking and waiting for it to go off. The orgasm: the paintings’ reception, their purchases, their status as legend. A night to remember.

The orgasm, in French, is le petit mort. Even in the wittiest, prettiest, and gayest of the Hollywood portraits, stubborn traces of death linger. Of course, the Marilyns, so the story goes, were made as part of the Death and Disasters series—an idea suggested to Warhol by the mover-and-shaker-curator Henry Geldzahler. The image of Marilyn is taken from a promotional headshot of Monroe in Henry Hathaway’s neat, brutal noir-in-color, Niagara (1953); yet nothing in the photograph signifies Marilyn’s shrewd, nuanced performance as Rose Loomis in that film: no Joseph Cotten, no cabins, no raging falls under which doomed lovers meet. “This is her,” the photo blankly, blaringly says. And Warhol made the Lizes, so the story also goes, when he was sure Taylor was about to die—from a sudden bout of pneumonia during the making of Cleopatra that hospitalized her, bringing the film’s already rocky shoot to a grinding halt. But Warhol’s blasé front when asked what compelled him to fill his first Pop shows in 1962 New York with the visages of these stars is typical, perhaps closer to the awful truth: “I was just making fabrics.”12 Indeed, Monroe and Taylor and Presley are just like different cloths that can be bought in varying shades to please the prospective collector. In the age of mechanical reproduction, once the photograph is taken one can do anything with it, regardless of the subject’s consent in life or death. Frightening. So it goes with the cults around Hollywood stars, where actors and actresses are endlessly discussed, their images cut and fetishized (today they are memed), leaving them as a queer race of walking-dead symbols. In this respect perhaps the key influence on Warhol was Edgar Morin, the celebrated French sociologist who teased out this quality in stark terms in his 1957 book The Stars, which occupied a privileged place on the artist’s vast bookshelf. In The Stars, Niagara is held up as an example of the star’s postwar renaissance: “Marilyn Monroe, the torrid vamp of Niagara, naked under her red dress, with her ferocious sexuality and her killer face, is the symbol of the star system’s revival.”13

It’s key to remember: Andy loved the artificial, absurd, over-the-top mythos of the movies. To many, Presley as an actor is a bad joke. But this joke is what turns Andy on. So the resultant work (whether a single Elvis or Eight Elvises, 1963) ends up running away from the initial flash of inspiration, i.e., a frighteningly and unusually remarkable performance by Presley as Pacer Burton, a half-white, half-Kiowa rancher who finds himself torn between his two worlds. The film, Flaming Star, is equally remarkable; it was directed by Don Siegel, praised by the critic Manny Farber as “a manipulative sock-bang director” and “a determinedly lower-case, crafty entertainer.”14 Surely these are pluses to the cinephile, the historian, the nostalgic, and the priest of remembrance.

Andy was only one of these, the first. Everything else he did was decidedly in the moment, unheedful of his past, unconcerned beyond the headlines of a day. This, ironically, gives longevity to his film paintings—let alone his extraordinary films, wherein he acted successfully in the deranged parody role of a studio head à la David O. Selznick, and which Gary Indiana has identified as “his richest body of work.”15 In their curious mixture of pathos, humor, Zen calm, and loving acceptance of the nothing as if it were the flibbertigibbety Katharine Hepburn to Warhol’s stoic Spencer Tracy, the film work of Warhol reflects the crazy beauty of modern life itself.

1 “I like all kinds of films except animated films, I don’t know why, except cartoons. Art and film have nothing to do with each other: film is just something you photograph, not to show painting on. I just don’t like it but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong.” Andy Warhol, in “Nothing to Lose: Interview with Andy Warhol by Gretchen Berg,” Cahiers du Cinéma in English, no. 10 (May 1967): 42. Repr. in Michael O’Pray, ed., Andy Warhol: Film Factory (London: British Film Institute, 1989), p. 58.

2 See Blake Gopnik, Warhol (New York: HarperCollins, 2020), p. 26.

3 Manny Farber, “Underground Films,” in Farber on Film: The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber, ed. Robert Polito (Washington, DC: Library of America, 2009), p. 488.

4 See Gopnik, Warhol, p. 26.

5 Ibid., p. 27.

6 Ibid., p. 26.

7 Not to mention Parker Tyler’s status as the idol of Gore Vidal’s novel Myra Breckinridge (1968): Myra is entranced by Tyler’s theories on Hollywood stars as the modern-day equivalent of Greek gods and goddesses.

8 Gopnik, Warhol, pp. 62–63.

9 “Coming of Age in Celluloid-Land,” Life, April 13, 1962, p. 40.

10 John Giorno, Great Demon Kings: A Memoir of Poetry, Sex, Art, Death, and Enlightenment (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020), p. 73.

11 John Waters, “Blue-Collar Liz,” in Warhol: Liz (New York: Gagosian, 2011), p. 104.

12 Warhol, quoted in Gopnik, Warhol, p. 283.

13 Cited in ibid., p. 282. My translation, however, from the French original: Edgar Morin, Les Stars (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1957).

14 Farber, “Don Siegel,” 1969, in Farber on Film, pp. 675–76.

15 Gary Indiana, “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” The Village Voice, May 5, 1987. Repr. in O’Pray, ed., Andy Warhol: Film Factory, p. 185.

Artwork © 2025 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Carlos Valladares is a writer and critic from Los Angeles. He studied film at Stanford University and began his PhD in History of Art and Film & Media Studies at Yale University in fall 2019. He contributes regularly to Art in America, n+1, and frieze. He lives in New York. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

The Fall 2025 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Andy Warhol’s Blue Liz as Cleopatra (1962) on the cover.

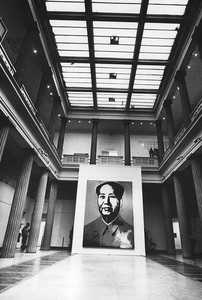

The Fall 2024 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Andy Warhol’s Mao (1972) on the cover.

Jessica Beck examines Andy Warhol’s return to painting in the 1970s, focusing on the artist’s Mao series.

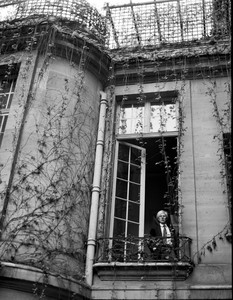

Andy Warhol’s Insiders at the Gagosian Shop in London’s historic Burlington Arcade is a group exhibition and shop takeover that feature works by Warhol and portraits of the artist by friends and collaborators including photographers Ronnie Cutrone, Michael Halsband, Christopher Makos, and Billy Name. To celebrate the occasion, Makos met with Gagosian director Jessica Beck to speak about his friendship with Warhol and the joy of the unexpected.

In this video, Jessica Beck, director at Gagosian, Beverly Hills, sits down to discuss the three early paintings by Andy Warhol from 1963 featured in the exhibition Andy Warhol: Silver Screen, at Gagosian in Paris.

Against the backdrop of the 2020 US presidential election, historian Hal Wert takes us through the artistic and political evolution of American campaign posters, from their origin in 1844 to the present. In an interview with Quarterly editor Gillian Jakab, Wert highlights an array of landmark posters and the artists who made them.

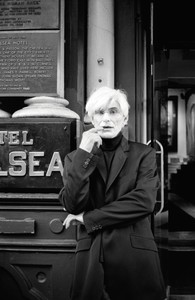

Raymond Foye speaks with the actor who impersonated Andy Warhol during the great Warhol lecture hoax in the late 1960s. The two also discuss Midgette’s earlier film career in Italy and the difficulty of performing in a Warhol film.

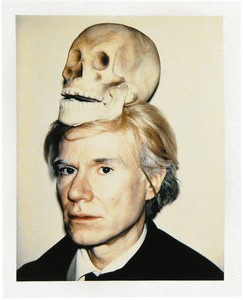

Jessica Beck, the Milton Fine Curator of Art at the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, considers the artist’s career-spanning use of Polaroid photography as part of his more expansive practice.

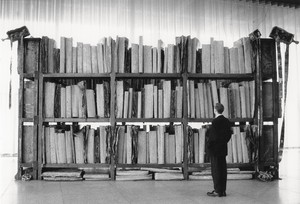

Rare-book expert Douglas Flamm speaks with designer Norman Diekman about his unique collection of books on art and architecture. Diekman describes his first plunge into book collecting, the history behind it, and the way his passion for collecting grew.

Gwen Allen recounts her discovery of cutting-edge artists’ magazines from the 1960s and 1970s and explores the roots and implications of these singular publications.

James Lawrence explores how contemporary artists have grappled with the subject of the library.

The Winter 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a selection from Christopher Wool’s Westtexaspsychosculpture series on its cover.